STATEMENT OF TEACHING PHILOSOPHY

Anne Marie Champagne

>> DOWNLOAD <<

Overview of Teaching Philosophy

From our first breath until our last, we are learners. We acquire knowledge, apprehend skills, grapple with new ideas and concepts that shape our attitudes, beliefs and values, and we marshal what we have learned to solve problems in our individual lives and in the communities in which we live. I believe, therefore, that learning is a dynamic, interactive, lifelong process, one that directly transforms our minds, hearts, and bodies and the social relationships through which they are woven.

It is precisely my regard for these interrelations – between the cognitive, the emotional, the behavioral, and the social – that forms the educative ground of my instructional goals. Learning is not simply a matter of competency, it is also a matter of cultivation—cultivating critical thinking and creative problem-solving skills, and more than this, cultivating oneself as a global citizen. Thus, one of my primary goals as a teacher is to ensure that my students examine the world empirically as well as theoretically. This means that in addition to mastering concrete skills and core competencies, I want my students to learn how to interrogate and evaluate content, to approach the familiar with fresh eyes and draw on what they already know in order to identify patterns, interpret the unfamiliar, and construct new knowledge that is uniquely their own but also visible to and shareable with others and adaptable to old as well as new contexts.

The Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that contemplation provides the basis of a good life.[1] He was onto something: contemporary education research findings suggest a positive correlation between educational attainment, subjective well-being, and improved quality of life. [2] Providing students equal access to a high-quality education is therefore paramount, and it is one of the charges of a good teacher. Yet one thing my experiences as both a student and teacher have taught me is that socioeconomic disadvantages, structural inequalities, and even cultural variation and learning differences among students can impede the fulfillment of this charge. For this reason, my teaching style is decidedly student-centered.

What does a student-centered approach to teaching entail? For me, my teaching style is where my pedagogical orientation, which attends to the cognitive, emotional, behavioral and social aspects of learning, and my instructional goals, of competency-based mastery balanced by self-cultivation, come together. Recognizing that students are neither blank slates nor open vessels, but rather full human beings, each with their own sophisticated biography and thus unique set of gifts, challenges, aspirations and fears, my teaching style is responsive to the tenor of the classroom but also to the needs of each student. What I recognize in each student before me is potential and success. Granted, many teachers and administrators recognize the former, but how many are able to recognize and engage with the latter? Drawing upon my own experiences as an instructor and student support service provider, I shall explain in the sections that follow what I mean by recognizing not only potential but also success in our students.

Providing Educative Experiences that Acknowledge and Promote Student Success

I will never forget the day I overheard high school teachers speak of their students as hopeless failures. I knew some of these students, having worked among them in the classroom, providing support services to their peers. Knowing something of their lives as well as academic track records, I knew otherwise: they were not failures. Some were taking care of younger siblings, waking at the crack of dawn to make breakfast, pack lunches, rouse their little sisters and brothers from sleep to bathe them, dress them, and escort them to school, all before heading to school themselves in time for first period class. Some took care of their siblings because their parents were in prison, were suffering from addiction, or had to work two to three jobs to make ends meet. Some students were caring for ailing grandparents, working full time to supplement household incomes, or even in some cases living on their own.

As I saw it, the very fact that these students showed up to class, eager, if not entirely prepared to learn, was in of itself a success, one deserving of acknowledgment and commendation. This extended awareness of students’ lives shapes my understanding of my role and efficacy as a teacher, both at the high school and university levels (many of my college students and mentees had similar stories of hardship to share, and adversity is not class-bound). As much as I believe classrooms to constitute sacred spaces of learning, I equally believe that that these spaces must be made inclusive if deep learning is to occur. The inclusivity of which I speak cuts across multiple domains and involves trust. It means working with rather than neglecting the internal (cognitive and emotional) and external (behavioral and social) forces governing students’ lives. Some of these forces will impose constraints upon student learning. Not all constraints and contingencies can be resolved, but an attentive teacher can anticipate them and help students advocate for and negotiate appropriate accommodations.

In the college classroom, I endeavor to foster this spirit of inclusivity and trust from day one. I begin by having my students fill out confidential note cards on which I ask them to list, in addition to generic demographic information, their preferred names and pronouns, an interesting anecdote or fact about themselves, and anything else I should know, particularly anything that might impact their academic performance. The addition of these biographical questions opens the lines of communication between the student and me, reinforcing our mutual duty of care to learning outcomes.

Furthermore, I let my students know that I am not just an instructor, but that I am also a liaison, someone who will help them develop effective learning strategies and facilitate pathways of discovery. This facilitation includes responding to queries in a timely and helpful manner, directing students to appropriate learning resources and services, and allowing for diverse forms of class participation. Whereas some students prefer to speak, others prefer to write, bring in outside materials to share, or draw. I respect these and other participation styles while also offering students opportunities to experiment with different modes of participation that stretch them beyond their comfort zones. For instance, I will have students who avoid speaking in class use their voices in a small group activity, and I will ask students who normally speak to act as the group scribe. Role-switching gives students a chance to develop new skills in a low-stakes environment where risk-taking, feelings of awkwardness, and failure are accepted. It is important for students to know that learning and mastery are not instantaneous; they are processes that involve repetition and practice.

I believe that we learn as much, if not more, from our failures as we do from our successes. I try to model this understanding for my students at all points of the learning process: as we analyze texts, participate in group or lab activities, take assessments, and ask questions. One way I do this is by asking students to identify the weaknesses and strengths of a text or theory and, too, the author’s underlying biases. We then discuss how these contribute to the author’s takeaway point. Could we have anticipated the conclusion from the start or did we make adjustments along the way as new information was introduced? Rather than give students the answers, I adopt a Socratic method of cooperative dialog to stimulate critical thinking. As I advise my students at the start of class, for this method to be successful, we must each exercise graciousness and courtesy toward our fellow peers. This includes inviting honest questions and comments with the understanding that knowledge and social awareness are not evenly distributed and that the mechanics of how we formulate a question or comment can be improved with constructive feedback. Therefore, rather than judge a person by their words alone, we should give them the benefit of the doubt and weigh more heavily their sincerity to learn and grow. Thus, I endeavor to create a supportive learning environment where students feel welcomed to explore, stumble, succeed, and discover.

Curriculum Design and Student Assessment

The notion that we can learn as much from what we get wrong as from what we get right informs my approach to curriculum design and student assessment. As a university teaching fellow, I always took the time to offer students individual feedback on their papers (the traditional form of assessment in the humanities and social sciences), making comments and suggestions on matters of cohesion and coherency, methodology and argumentation, formatting and citation styles, and basic grammar, among other elements of good writing. For me, grading is not the mere calculation of a final score; it is an opportunity to provide constructive feedback that reinforces students’ learning goals and emerging insights while also offering them clear guidance for improvement. It is important to me that I take advantage of this instructional opportunity, not in the least because writing well is fundamental to high academic achievement and to securing future internship, scholarship, and job opportunities.

In regards to curriculum, for a lecture or discussion section, I generally follow backwards design. First, I emphasize key learning goals and concepts, noting their linkages to previous lectures. (I often begin with a specific discussion question that I have submitted to the students ahead of class.) Next, I introduce the general principles of the day’s lecture, following up with evidence, details and facts illustrated through interactive examples and/or student activities. Last, I conclude with a brief summation, highlighting the big takeaways, and then open the floor to final questions and comments. In a seminar class, I may prompt students to conduct a close reading of a text for specific themes, which I will have them connect to previous readings, core concepts, and theories.

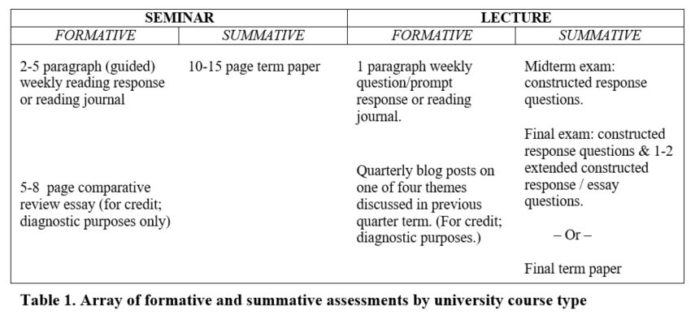

Though I have assisted university instructors with exam design, I have not yet had the opportunity to design my own assessments, except assignment prompts and rubrics. I have, however, given considerable thought to how I would approach student assessment in the courses I will teach. Having learned from my own experiences proctoring and grading final exams and term papers, I believe that both seminars and lecture courses should strike a balance between formative assessment and summative assessment (see Table 1 below).

The formative assessments I propose give students a chance to demonstrate individual strengths and knowledge and critically engage with course material on their own terms, albeit within a structured, purposeful framework (e.g., in response to a question, a guided prompt, or paper assignment). In addition to holding students accountable for weekly readings, reading responses may be posted to a class forum to stimulate online and in-class discussion. These quick formative assessments are intended to (a) emphasize, for students, core themes, ideas and concepts which may appear later on a test or could be incorporated into a term paper, and (b) highlight, for me, the concepts with which students are having the greatest difficulty, so that I may adjust in-class discussion and lecture content accordingly.

Diagnostic formative assessments are centered on writing skills. Since essays and research papers often comprise the greatest percentage (sometimes 100%) of a college student’s course grade, I believe it is important for teachers to assess and address the strengths and weaknesses of students’ writing, and to do so well in advance of the first summative writing assignment deadline. As for myself, I plan to use this knowledge to incorporate brief writing tutorials in class that address students’ weaknesses and grade student papers based on demonstrated improvement, among other criteria.

When and where a course requires summative examination, I will endeavor to design exams that strictly test students’ knowledge of course content, as opposed to, for instance, whether they are paying attention to the wording of the question itself. My goal is to test knowledge—what my students have learned. Summative testing is neither the place for trick questions nor for surprising students with new material or an unfamiliar question format. Realizing that not all students are “good” test takers, and that anxiety levels are generally high before an exam, one of my goals as a teacher is to set appropriate test-taking expectations in an effort to reduce student anxiety. For this reason, I impose upon myself a “no surprises” rule. I contend that reading responses and in-class discussions are the appropriate places for surprise and spontaneity. In support of my “no surprises” rule, I shall make comprehensive study guides available to my students (with tips for success), and I will conduct exam question simulations in class on a regular basis, which will allow students to crowdsource possible answers, ask questions, receive my expert feedback and familiarize themselves with the test’s format.

Furthermore, with respect to test questions themselves, I prefer short constructed-response questions to multiple-choice and extended-response questions to open-ended essays. My preference derives from a belief that exam questions should be clear and direct, test student’s knowledge of core themes, and require applied critical thought. Taking inspiration from Prof. Henry Cowles, whom I assisted as a teaching fellow in the fall of 2015, a typical exam question might consist of an exemplary passage from one of the course readings in response to which students must identify one or more of the following: (a) theory or key concept, along with a brief definition; (b) one to two related concepts/readings; (c) why, in their opinion, this theory or concept matters; (d) relevant time period; (e) article title or author. Such questions, I believe, encourage students to stay abreast of and critically engage course readings and use passive recall (the presentation of quoted material) to elicit higher-order thinking.

Room to Grow: It is Our Willingness to Make Mistakes that Drives Inner Excellence [3]

Of course, what I have outlined here is an ideal, one that I carry with me each day into the classroom yet have fallen short of achieving on several occasions. Teaching is itself an educative process. Every day I interact with students, I am reminded of this and that there is room for improvement—room for me to grow. Among my weaknesses as an instructor, I would cite the following:

- Speaking too quickly. Sometimes I present too many ideas all at once or do not allow students sufficient time to process and respond to extemporaneous questions.

- Dropping disciplinary buzzwords. Sometimes I forget that not all students will have completed the assigned readings before a class, or that coming from an outside discipline, some students may lack sufficient background knowledge to understand their use.

- Neglecting to explain all suggestions or comments. Sometimes I will sacrifice detailed feedback for the sake of expediency, especially when I am up against a grade submission deadline.

A portion of the above is the natural consequence of being a teaching fellow, that is, of having limited autonomy or in some cases limited contact with students. An instructor of record may, for example, specify an agenda for a weekly section discussion that incorporates more material than can reasonably be covered in 50 minutes. Given the contingencies of open group discussion, this may cause me to rush ahead to the next point in order to move the discussion along. In courses for which I have acted as a grader, I am not always aware of whether students have had an opportunity to read and discuss assigned readings. As a consequence, I may include disciplinary jargon in my grading comments under the false presumption that these terms have already been introduced and discussed in class.

These considerations notwithstanding, I recognize that my weaknesses as an instructor are not restricted to the limitations of being a teaching fellow. Pacing myself, being an active listener, taking the time to define terms and explain the rationale behind my comments, or, when I cannot, providing links to relevant resources, and knowing which topics and questions are of the essence and which can be tabled for later—these are the educative teaching practices I must foster in myself and in the classroom going forward, for what is true of students is also true of teachers: our weaknesses can only be turned into strengths with discipline. It is thus with great enthusiasm that I look forward to engaging in this noble discipline with my students for many years to come.

—-

[1] Aristotle, Ross, W. D., & Brown, L. (2009). The Nicomachean ethics. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

[2] Edgerton J.D., Roberts L.W., von Below S. (2012) Education and Quality of Life. In: Land K., Michalos A., Sirgy M. (eds) Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life Research. Dordrecht, Springer.

[3] Hohne, K. (2015) The essential I Ching: 64 degrees of nature’s wisdom. Carnelian Bay, Way of Tao Books.